Camille Fournier, author of “The Manager’s Path” emphasizes the importance of one-on-one meetings, also referred to as one-on-ones. These meetings help foster a strong working relationship with your direct manager. They provide ample opportunity to discuss goal setting, performance review, and career development. In a remote work environment, the value one-on-ones provide extends beyond your manager and to your immediate team members. Regular one-on-ones with your teammates:

- Humanize individuals on the other side of the screen

- Facilitate knowledge sharing, mentorship, and cross-training

- Enable collaborative problem solving and support

- Provide opportunity for feedback and the free exchange of ideas

- Build relationships with other remote members of your team

- Help identify systemic issues or concerns within a team or organization

- Provide a platform for addressing conflicts / disagreements that may arise

While peer one-on-ones can provide a lot of value, a big argument against them is that they require a lot of time and can cost a lot of money. In this post, we’ll take a deeper look into the time commitment and cost for peer one-on-ones.

Observations

Before diving into the time and cost of one-on-ones, let us first consider how many meetings happen given a team size. We do this by simply enumerating the meeting pairs that occur.

| Team Size | Team Members | Number of one-on-ones | Meeting Pairs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | (A) | 0 | |

| 2 | (A, B) | 1 | (A|B) |

| 3 | (A, B, C) | 3 | (A|B, A|C, B|C) |

| 4 | (A, B, C, D) | 6 | (A|B, A|C, B|C, A|D, B|D, C|D) |

As some may have noticed, our chart starts to show an arithmetic sequence, similar to like the Fibonacci sequence:

f(x) = f(x - 1) + f(x - 2) where f(0) = 0 and f(1) = 1.

Similarly, we can express the number of one-on-ones needed for a team based on team size using the following equations:

f(x) = (x-1) + f(x - 1) where f(0) = 0 and f(1) = 0

OR

f(x) = x * (x-1) / 2

Using this information, we can extrapolate data for various team sizes and visualize how the number of one-on-ones scale as the team grows.

Now that we understand the relationship between a team’s size and the total number of one-on-ones, we can take a closer look at time.

Time Commitment

We can think of time commitment in one of two ways: for an individual, or for the collective team. To show this, let us consider the following equation which computes the time commitment based on values for the collective team.

T(t, x, H) = (f(x) * t * 2) / (x * H * 60) where t is the duration of one-on-ones (in minutes), x is the team

size, H is the number of hours in a given week, and f(x) is the number of one-on-ones.

As you can tell, this equation is a bit complicated. Luckily, we can plug in our f(x) equation and reduce it to get a much simpler one (which also happens to focus on the individual).

T(t, x, H) = ((x - 1) * t) / (H * 60) where t is the duration of one-on-ones (in minutes), x is the team size,

and H is the number of hours in a given week.

Using this simplified equation, we can now compute time commitment given an associated team size.

t = 30 minute one-on-ones, H = 32 hour week

It is important to note that while this graph appears linear, it is not. Using this chart, we can now estimate the time commitment required for a given team size. For example, if you have a 4 person team plus a manager you’re looking at spending about 6.25% of your time in one-on-ones. If your company has a 32 hour work week like CrabNebula, that comes out to be 2 hours per person, or 10 hours across the entire team.

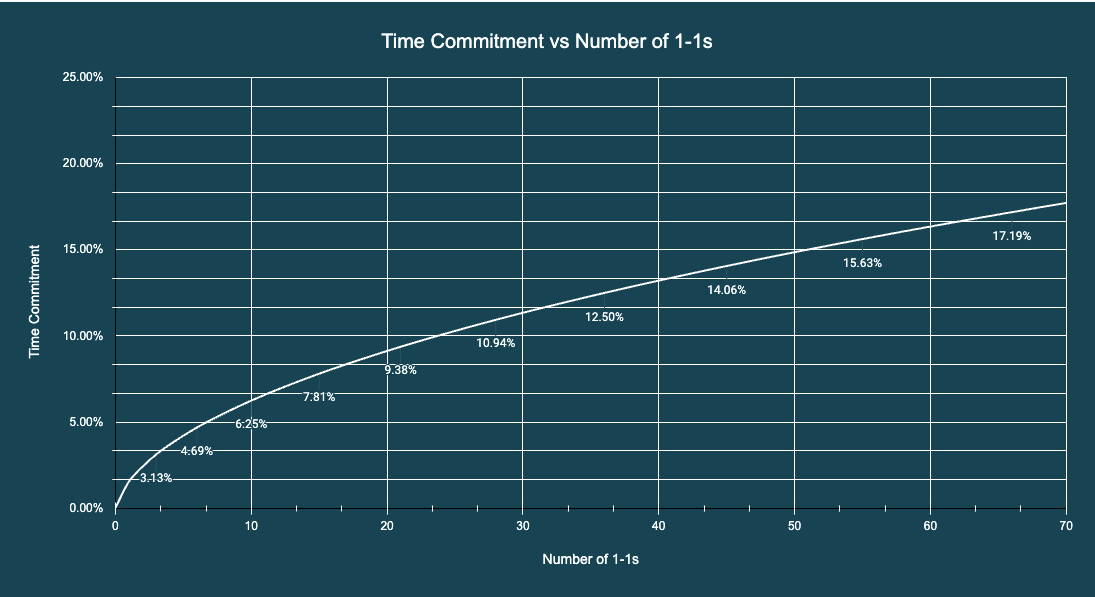

Next, let’s plot time commitment against the total number of one-on-ones. This will show how variances in team sizes distribute along the graph.

t = 30 minute one-on-ones, H = 32 hour week

One immediate thing that stood out in this graph is the density of data points in the lower ⅓ (less than 20 one-on-ones). This section alone accounts for teams up to size 9. Meanwhile, any team over the size of 9 falls in the upper ⅔ (more than 20 one-on-ones). This seems to indicate that teams of size 8 or smaller help keep variations in number of one-on-ones to a minimum (i.e. under 10% time).

Monthly Cost

Time and cost often go hand in hand with one another. Part of the challenge in sizing a team is balancing the time commitment required for its operation against the total cost. Using the time commitment in the charts above and that salary, we can compute monthly cost as a function of the team size.

Based on an average salary of $100k USD

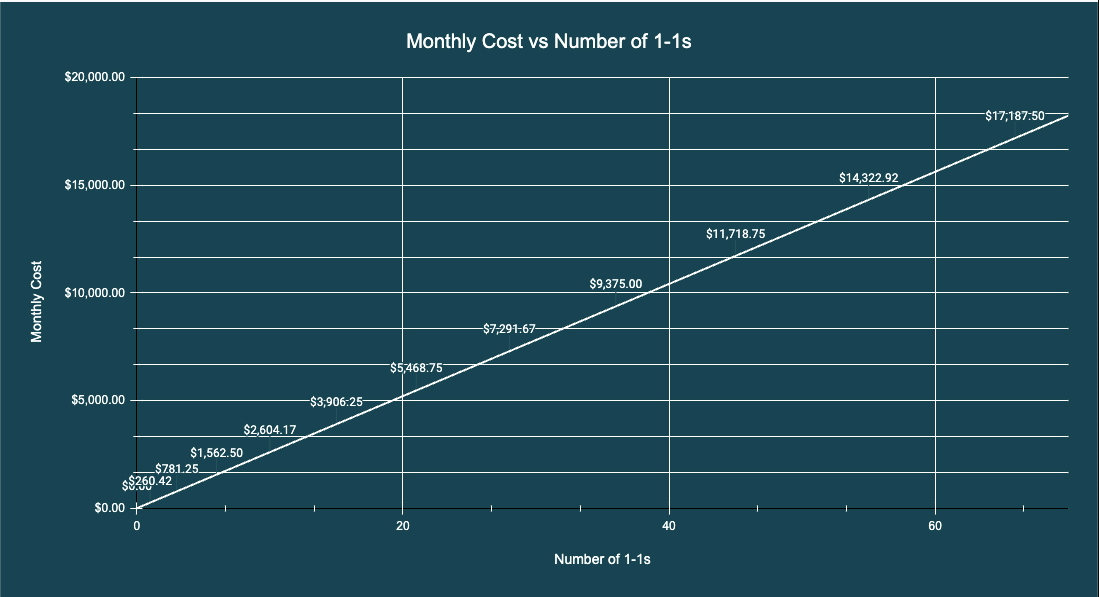

This approach is by far the easiest to understand as the cost follows the same curve as the number of one on ones. Similarly, we can plot the cost against the number of one-on-ones. This shows us how cost changes relative to the increase or decrease in one-on-ones.

As expected, we see a linear relationship between the number of one-on-ones and their associated cost. And yet, each graph is insufficient on their own. We need to balance cost against time.

Balance

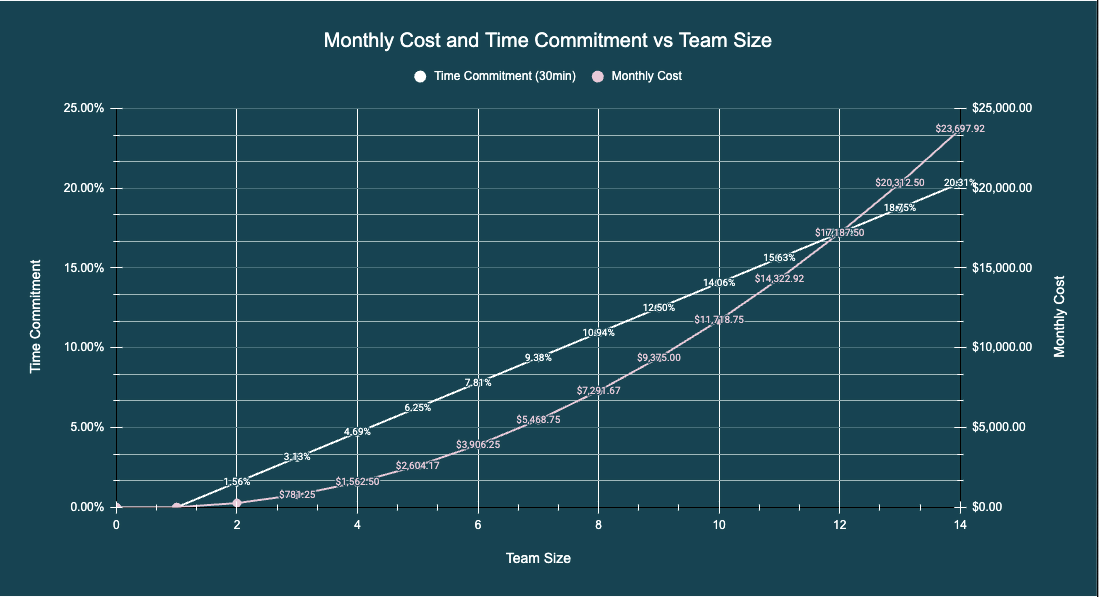

How many is too many? Some might say that the amount of time spent in meetings would be the biggest influencer in determining when a team is too large. Others may argue that the cost involved is the major influencing factor. Using the data we charted in the two previous sections, we can plot cost and time as a function of both team size as well as number of one-on-ones. Using these graphs we can balance the time commitment against the associated cost.

t = 30 minute one-on-ones, H = 32 hour week

Based on an average salary of $100k USD

The software industry often refers to “2 pizza teams” as an ideal size. At the same time, every company has a different idea around how big a “2 pizza team” actually is. For example, Amazon often talks about this as being anywhere from 6 to 10 people, with an average around 8. Martin Fowler suggests this can be anywhere from 5 to 8 people with up to a maximum of 15.

Given these two data points, let’s estimate that most “2 pizza teams” fall around 8 people. An 8 person team would have a total of 28 one-on-one meetings, thus an estimated time commitment of 10.94%, and an estimated cost of $7291.67. Assuming a 32 hour work week, members of a “2 pizza team” should expect to spend about 3.5 hours of their time in one-on-one meetings.

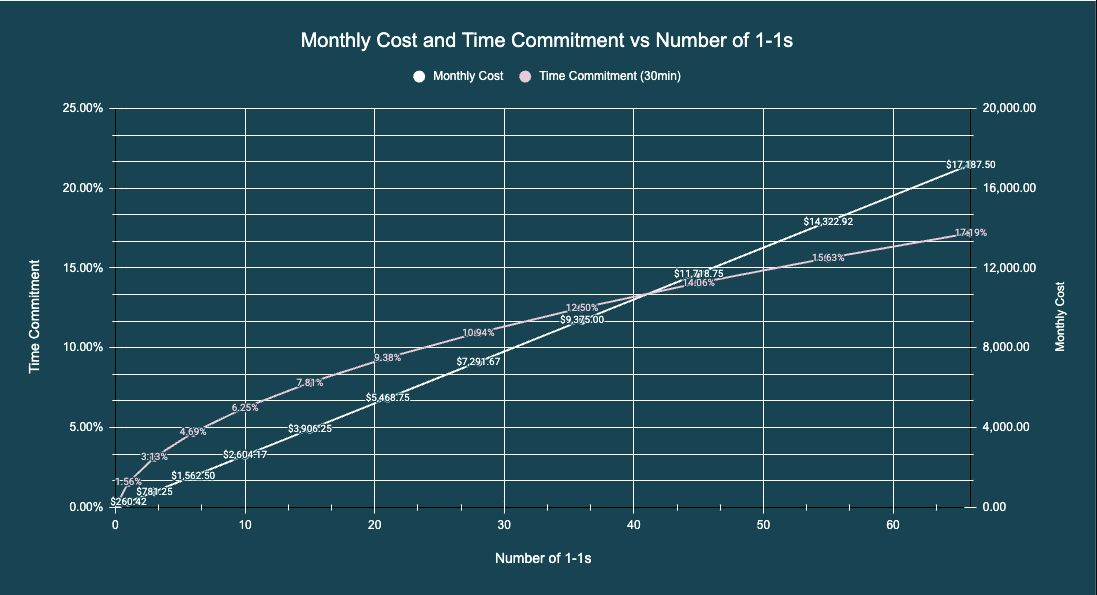

It’s important to remember that this value represents a relative maximum time commitment and cost. This is due to variations in interactions between team members. Some team members may prefer to meet every other week instead of every week. One-on-ones between certain team members may not occur (i.e. someone doing hardware development may not interact with someone doing graphic design or marketing). Using a graph similar to the one above, we can better understand changes in time commitment and cost relative to the number of one-on-ones.

t = 30 minute one-on-ones, H = 32 hour week

Based on an average salary of $100k USD

Conclusion

Answering the question of “How many is too many?” depends on the work environment you’re in. To determine these graphs for your company, plug in your one-on-one duration, working hours (H), and average salary. This will provide you with a baseline for making similar assessments.

For CrabNebula, an ideal “2 pizza team” is actually closer to 6. This keeps the core team close and tightly connected, while also providing flexibility for each member. This flexibility allows members of the team to self-select other individuals they want to have one-on-ones with. It’s important to remember that working relationships develop based on proximity AND interest. By providing flexibility, it allows engineers to meet with individuals with similar interests.

30 minutes tends to be the preferred length of time for one-on-ones. That’s not to say longer one-on-ones can’t occur, but they should be more the exception and not the rule. If you’re having trouble keeping them to 30 minutes, you can try augmenting your meeting time with additional opportunities for collaboration. For example, engineers on my team are encouraged to start spontaneous meetings for paired programming. This way, they’re not left feeling stuck on a problem until the next time the team meets. Instead, they can hop on a call with an expert within the company to work through the problem they’re facing. Another solution we employed is a weekly workshop session. This allows team members to bring bigger items to the table for discussion that have broader implications for the team at large.

Finally, a manager should never discourage or terminate one-on-ones between members of a team. I’ve worked at several companies where this has happened and it’s only had a negative impact. The team loses connection with one another, leaving members feeling isolated and disconnected from their work. Conversely, a manager shouldn’t force one-on-ones between two team members who do not work well together. There may be moments where the two may need a mediator to resolve issues, but forcing two people to meet when neither of them want to is a recipe for disaster.

Overall, one-on-ones provides significant value to teams operating in a remote work environment. While there are some drawbacks, the benefits outweigh the costs.

Reference

- The Google Sheet containing all the data backing this blog post. Please feel free to make a copy and update for your company! You should just need to plug in your variables in the upper section on the data sheet.